prasad1

Active member

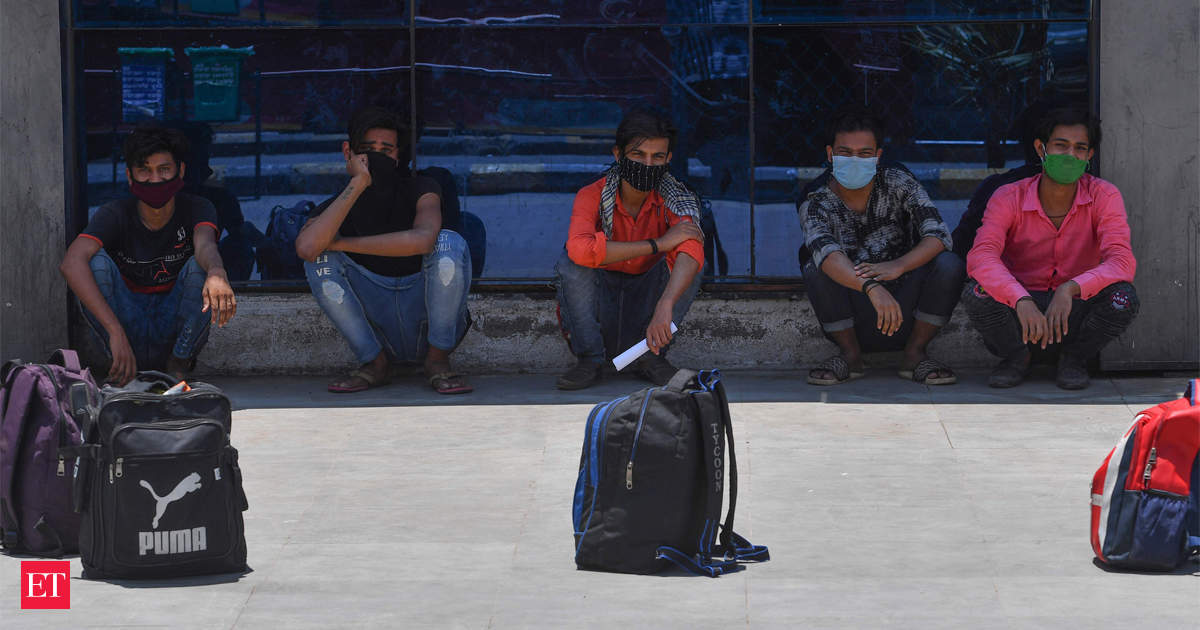

Migrant workers, dismissed by employers, enjoying no protection from their governments, often thrown out of their accommodation by their landlords, in urgent need of food transport and money, have been driven by desperation to walk home.(Raj K Raj/HT PHOTO)

Last Sunday, a friend of mine was in a group which was driven on official business from Delhi to Lucknow. As I have not seen a single report of a long drive and I am locked down in a containment area, I asked him to take notes on what he saw. He was not allowed to stop and interview anyone. All along the 416 km route, he saw migrant workers and their families walking to their homes, most of them were in groups, some alone. The old hobbled supported by sturdy sticks; some younger men, drenched in sweat, for it was a sunny Sunday, carried heavy bags strapped to their backs; others carried sacks on their heads. Babies and young children were held in the arms of their parents, older children clasped their parents’ hands. At a village called Brijghat in Hapur district, the police manhandled young cyclists trying to get past a barricade. My friend’s vehicle was stopped at barricades and checked by the police each time he crossed the borders between districts. All dhabas and shops were closed. Drinking water was only provided at two places. At one place, Sikhs had established a langar and were providing food for the walkers. Within Lucknow, the police checking was intensified but walkers were still to be seen on the ring road.

Nearly six weeks after the first lockdown was announced, this was the scene on the road between the capital of India and the capital of its most populous state. Migrant workers, dismissed by employers, enjoying no protection from their governments, often thrown out of their accommodation by their landlords, in urgent need of food transport and money, driven by desperation to walk home. It is a scene many have described as reminiscent of the migration at Partition. This is the outcome of the largest and one of the strictest lockdowns in the world enforced during the coronavirus disease crisis — a lockdown that has been widely applauded internationally.

Why has the outcry against this suffering inflicted on men and women who are more than 90% of India’s workforce been so muted?

India’s migrant workers deserve better than this, writes Mark Tully

Why has the outcry against this suffering inflicted on men and women who are more than 90% of India’s workforce been so muted?

Because the opposition is dead and being systematically killed.

The upper and middle class does not care about the plight of the poor.