prasad1

Active member

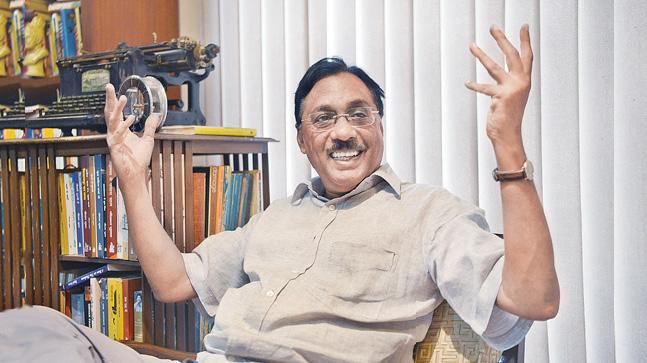

Pavan Verma in his writing believes:

What they don't understand is that Hinduism itself teaches you to be secular."

Taking the argument further, he adds, "We have to know that Upanishads were penned down over 4,000 years ago in a dialogic manner in forest academies between gurus and disciples; subsequently, in the Brahma Sutras, the commentaries would first have the views of the opponents, followed by the position of the Vedanta." Hinduism could reconcile the differences, including those with Charvakas and tantriks, he says, through shastra has, debates and dialogues. "One person encompassing all these civilizational values was Shankaracharya," he says explaining the book's raison d'etre.

Calling Shankara a "true rebel", Varma reminds how the monk called a Chandala he met in Kashi his guru. "For me, it was an eye-opener to see Shankara, a Namboodiripad Brahmin, refuting the caste system. He, in fact, went to the extent of not even accepting the authority of the Vedas, the Varnasrama system, and the Char Dham," he says. The monk's relationship with his mother also showed his rebellious streak. For, being a sannyasi didn't stop him from serving his mother at the fag end of her life. "Being the only child, he came back from his renunciation to serve her.

Maybe his attachment with his mother was the reason for his Devi/Shakti worship, though he remained an avowed Vedantist all through his life," he reminds. For all his talk of 'nirgun' (attributeless) and 'nirakar' (abstract) God, and the world being an illusion, it was Shankara who set up 12 jyotirlingas, 18 shakti-peethas, and four Vishnu-dhaams to create all-India pilgrim centers that defined the nation as one civilizational entity.

Varma, however, doesn't see this as a contradiction. "Shankara divided the jnana marga (path of knowledge) into two levels - para vidya (higher knowledge), where the primary concern was the metaphysical comprehension of the absolute; and apara vidya (lower knowledge), where bhakti, yoga, and ritual were given legitimacy. He saw the latter as part of the preparatory steps to move from apara to para vidya."

Shankara, for the author, is also a reminder of how sophisticated the Indian thought system was, though he has nothing but contempt for what he calls "the Dinanath Batra-style of scholarship", which invents flying machines and test-tube babies in ancient times. Terming India the "guiding light" of what he calls 'maulik jnana' (original thinking), Varma reminds us how at a time when scientists are not ruling out the possibility of multiverses, the notion of Brahman being infinite seems so contemporary.

"Shankara's concept of the Vedantic absolute, all-pervasive, beyond boundaries, and cosmic in scale, seems akin to the modern scientific interpretation of the space," he says, adding that Stephen Hawking could well have been the disciple of Shankara, had he been aware of Indian philosophical traditions. Ironically, it was Hawking who pompously claimed a few years ago that "philosophy is dead". And if one reads his book, The Grand Design, he - again paradoxically - appears closer to Shankara than to his counterparts obsessed with Newtonian determinism.

"Hawking might have been surprised to discover how much of what modern science has revealed, particularly in the areas of cosmology, quantum physics, and neurology, was anticipated by Shankara more than a millennium ago," signs off the writer-diplomat, cautioning on the growing culture of unrestrained shrill and 'dialogue lessness' in the otherwise argumentative nation.

www.indiatoday.in

www.indiatoday.in

What they don't understand is that Hinduism itself teaches you to be secular."

Taking the argument further, he adds, "We have to know that Upanishads were penned down over 4,000 years ago in a dialogic manner in forest academies between gurus and disciples; subsequently, in the Brahma Sutras, the commentaries would first have the views of the opponents, followed by the position of the Vedanta." Hinduism could reconcile the differences, including those with Charvakas and tantriks, he says, through shastra has, debates and dialogues. "One person encompassing all these civilizational values was Shankaracharya," he says explaining the book's raison d'etre.

Calling Shankara a "true rebel", Varma reminds how the monk called a Chandala he met in Kashi his guru. "For me, it was an eye-opener to see Shankara, a Namboodiripad Brahmin, refuting the caste system. He, in fact, went to the extent of not even accepting the authority of the Vedas, the Varnasrama system, and the Char Dham," he says. The monk's relationship with his mother also showed his rebellious streak. For, being a sannyasi didn't stop him from serving his mother at the fag end of her life. "Being the only child, he came back from his renunciation to serve her.

Maybe his attachment with his mother was the reason for his Devi/Shakti worship, though he remained an avowed Vedantist all through his life," he reminds. For all his talk of 'nirgun' (attributeless) and 'nirakar' (abstract) God, and the world being an illusion, it was Shankara who set up 12 jyotirlingas, 18 shakti-peethas, and four Vishnu-dhaams to create all-India pilgrim centers that defined the nation as one civilizational entity.

Varma, however, doesn't see this as a contradiction. "Shankara divided the jnana marga (path of knowledge) into two levels - para vidya (higher knowledge), where the primary concern was the metaphysical comprehension of the absolute; and apara vidya (lower knowledge), where bhakti, yoga, and ritual were given legitimacy. He saw the latter as part of the preparatory steps to move from apara to para vidya."

Shankara, for the author, is also a reminder of how sophisticated the Indian thought system was, though he has nothing but contempt for what he calls "the Dinanath Batra-style of scholarship", which invents flying machines and test-tube babies in ancient times. Terming India the "guiding light" of what he calls 'maulik jnana' (original thinking), Varma reminds us how at a time when scientists are not ruling out the possibility of multiverses, the notion of Brahman being infinite seems so contemporary.

"Shankara's concept of the Vedantic absolute, all-pervasive, beyond boundaries, and cosmic in scale, seems akin to the modern scientific interpretation of the space," he says, adding that Stephen Hawking could well have been the disciple of Shankara, had he been aware of Indian philosophical traditions. Ironically, it was Hawking who pompously claimed a few years ago that "philosophy is dead". And if one reads his book, The Grand Design, he - again paradoxically - appears closer to Shankara than to his counterparts obsessed with Newtonian determinism.

"Hawking might have been surprised to discover how much of what modern science has revealed, particularly in the areas of cosmology, quantum physics, and neurology, was anticipated by Shankara more than a millennium ago," signs off the writer-diplomat, cautioning on the growing culture of unrestrained shrill and 'dialogue lessness' in the otherwise argumentative nation.