prasad1

Active member

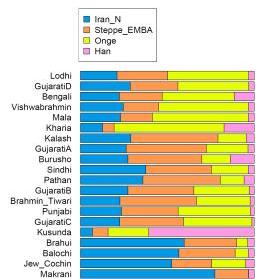

The modern-day Indians are not from the Indian subcontinent. There may not have been an Aryan invasion, but a slow migration of people from 3 different regions,

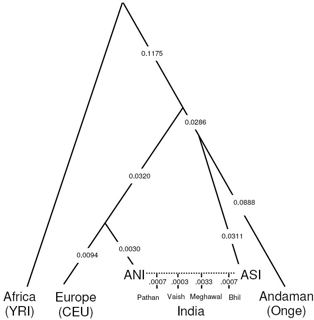

The Indian population originated from three separate waves of migration from Africa, Iran and Central Asia over a period of 50,000 years, scientists have found using genetic evidence from people alive in the subcontinent today.

The Indian Subcontinent harbours huge genetic diversity, in addition to its vast patchwork of languages, cultures and religions.

Researchers at the University of Huddersfield in the UK found that some genetic lineages in South Asia are very ancient.

The earliest populations were hunter-gatherers who arrived from Africa, where modern humans arose, more than 50,000 years ago.

However, further waves of settlement came from the direction of Iran, after the last Ice Age ended 10-20,000 years ago, and with the spread of early farming.

These ancient signatures are most clearly seen in the mitochondrial DNA, which tracks the female line of descent.

However, Y-chromosome variation, which tracks the male line, is very different, according to the study published in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

"Here the major signatures are much more recent. Most controversially, there is a strong signal of immigration from Central Asia, less than 5,000 years ago," said Marina Silva, co-author of the study.

"This looks like a sign of the arrival of the first Indo- European speakers, who arose amongst the Bronze Age peoples of the grasslands north of the Caucasus, between the Black and Caspian Seas," Silva said.

They were male-dominated, mobile pastoralists who had domesticated the horse - and spoke what ultimately became Sanskrit, the language of classical Hinduism - which more than 200 years ago linguists showed is ultimately related to classical Greek and Latin, the study found.

Migrations from the same source also shaped the settlement of Europe and its languages, and this has been the subject of most recent research.

The origin of the Indian population is an area of huge controversy among scholars and scientists.

A problem confronting archaeogenetic research into the origins of Indian populations is that there is a dearth of sources, such as preserved skeletal remains that can provide ancient DNA samples.

In the latest study, researchers used genetic evidence from people alive in the subcontinent today.

www.business-standard.com

www.business-standard.com

The Indian population originated from three separate waves of migration from Africa, Iran and Central Asia over a period of 50,000 years, scientists have found using genetic evidence from people alive in the subcontinent today.

The Indian Subcontinent harbours huge genetic diversity, in addition to its vast patchwork of languages, cultures and religions.

Researchers at the University of Huddersfield in the UK found that some genetic lineages in South Asia are very ancient.

The earliest populations were hunter-gatherers who arrived from Africa, where modern humans arose, more than 50,000 years ago.

However, further waves of settlement came from the direction of Iran, after the last Ice Age ended 10-20,000 years ago, and with the spread of early farming.

These ancient signatures are most clearly seen in the mitochondrial DNA, which tracks the female line of descent.

However, Y-chromosome variation, which tracks the male line, is very different, according to the study published in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

"Here the major signatures are much more recent. Most controversially, there is a strong signal of immigration from Central Asia, less than 5,000 years ago," said Marina Silva, co-author of the study.

"This looks like a sign of the arrival of the first Indo- European speakers, who arose amongst the Bronze Age peoples of the grasslands north of the Caucasus, between the Black and Caspian Seas," Silva said.

They were male-dominated, mobile pastoralists who had domesticated the horse - and spoke what ultimately became Sanskrit, the language of classical Hinduism - which more than 200 years ago linguists showed is ultimately related to classical Greek and Latin, the study found.

Migrations from the same source also shaped the settlement of Europe and its languages, and this has been the subject of most recent research.

The origin of the Indian population is an area of huge controversy among scholars and scientists.

A problem confronting archaeogenetic research into the origins of Indian populations is that there is a dearth of sources, such as preserved skeletal remains that can provide ancient DNA samples.

In the latest study, researchers used genetic evidence from people alive in the subcontinent today.

Indian population originated in 3 migration waves from Africa, Iran & Asia

Researchers at University of Huddersfield found some genetic lineages in South Asia are very ancient