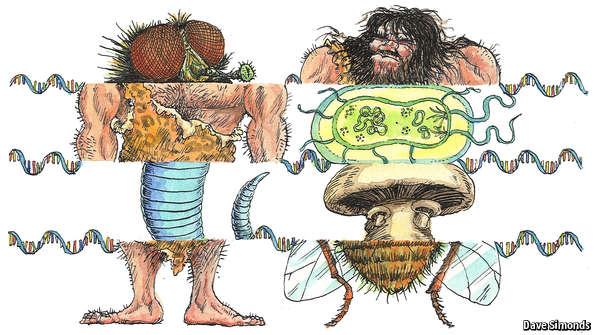

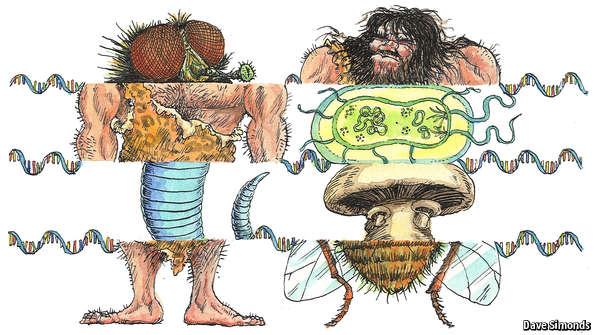

Interesting stuff! Human evolution is mysterious! But the gene theory has given substance to some fanciful stuff which are currently only in the realm of imagination! Did Humans evolve from algae, fungus & bacteria to other evolved species...Read this

Genetically modified people

Human beings’ ancestors have routinely stolen genes from other species

Mar 14th 2015

OPPONENTS of genetically modified crops often complain that moving genes between species is unnatural. Leaving aside the fact that the whole of agriculture is unnatural, this is still an odd worry. It has been known for a while that some genes move from one species to another given the chance, in a process called horizontal gene transfer. Genes for antibiotic resistance, for example, swap freely between species of bacteria. Only recently, though, has it become clear just how widespread such natural transgenics is. What was once regarded as a peculiarity of lesser organisms has now been found to be true in human beings, too.

Alastair Crisp and Chiara Boschetti of Cambridge University, and their colleagues, have been investigating the matter. Their results, just published in Genome Biology, suggest human beings have at least 145 genes picked up from other species by their forebears. Admittedly, that is less than 1% of the 20,000 or so humans have in total. But it might surprise many people that they are even to a small degree part bacterium, part fungus and part alga.

Dr Crisp and Dr Boschetti came to this conclusion by looking at the ever-growing public databases of genetic information now available. They did not study humans alone. They looked at nine other primate species, and also 12 types of fruit fly and four nematode worms. Flies and worms are among geneticists’ favourite animals, so lots of data have been collected on them. The results from all three groups suggest natural transgenics is ubiquitous.

To avoid getting bogged down in the billions of base pairs of an animal genome the researchers looked at what is known as the transcriptome. This is the set of messenger molecules, made of a DNA-like chemical called RNA, that pick up instructions on how to make proteins from genes in the nucleus and deliver them to the subcellular factories which turn those proteins out. Broadly speaking, each type of messenger RNA corresponds to a single gene. By looking at the messengers Dr Crisp and Dr Boschetti could be certain they were recording active genes and not stretches of nuclear DNA that had once been genes but now no longer work.

Useful immigrants

For every transcribed messenger, they searched the world’s databases, looking for matches. They excluded the immediate relatives of each of their three groups of animals (that is, no arthropods were compared with the flies, no vertebrates with the primates and no other nematodes with the worms). They then asked whether similar-looking genes to those in a transcriptome were found more often in other animals, or in non-animals. If the former, the most likely explanation would be that they were there by common descent from animal ancestors. If the latter, then, a horizontal gene transfer from species to species seemed the most probable explanation. On average, worms had 173 horizontally transferred genes, flies had 40 and primates had 109. Humans thus had more than the primate mean.

Many of the matches are to genes of unknown purpose—for it is still the case, more than a decade after the end of the human genome project, that the jobs of many genes remain obscure. But some human transgenes are surprisingly familiar. The ABO antigen system, which defines basic blood groups for transfusion purposes, looks bacterial. The fat-mass and obesity-associated gene, the effect of which is encapsulated in its rather long-winded name, seems to come from marine algae. And a group of genes involved in the synthesis of hyaluronic acid originates from fungi. Hyaluronic acid is a chemical that is an important part of the glue which holds cells together. (It is also a frequent ingredient of skin creams.)

Altogether, the researchers found two imported genes for amino-acid metabolism, 13 for fat metabolism and 15 which are involved in the post-manufacture modification of large molecules. They also identified five immigrants that generate antioxidants and seven that are part of the immune system.

This is quite a catalogue. If anything similar were inserted by genetic engineers into corn or cattle, there would no doubt be an outcry. In humans, however, they are doing a good job. It is fair to point out that many of them seem to have been cohabiting with the line that led to humanity for millions of years, and both sides have thus had ample time to adjust. Nevertheless there was once a moment for all of them when they were just as alien as a bacterial insecticide is in a maize plant or a herbicide-resistance gene is in a soyabean.

Horizontal gene transfer: Genetically modified people | The Economist

Genetically modified people

Human beings’ ancestors have routinely stolen genes from other species

Mar 14th 2015

OPPONENTS of genetically modified crops often complain that moving genes between species is unnatural. Leaving aside the fact that the whole of agriculture is unnatural, this is still an odd worry. It has been known for a while that some genes move from one species to another given the chance, in a process called horizontal gene transfer. Genes for antibiotic resistance, for example, swap freely between species of bacteria. Only recently, though, has it become clear just how widespread such natural transgenics is. What was once regarded as a peculiarity of lesser organisms has now been found to be true in human beings, too.

Alastair Crisp and Chiara Boschetti of Cambridge University, and their colleagues, have been investigating the matter. Their results, just published in Genome Biology, suggest human beings have at least 145 genes picked up from other species by their forebears. Admittedly, that is less than 1% of the 20,000 or so humans have in total. But it might surprise many people that they are even to a small degree part bacterium, part fungus and part alga.

Dr Crisp and Dr Boschetti came to this conclusion by looking at the ever-growing public databases of genetic information now available. They did not study humans alone. They looked at nine other primate species, and also 12 types of fruit fly and four nematode worms. Flies and worms are among geneticists’ favourite animals, so lots of data have been collected on them. The results from all three groups suggest natural transgenics is ubiquitous.

To avoid getting bogged down in the billions of base pairs of an animal genome the researchers looked at what is known as the transcriptome. This is the set of messenger molecules, made of a DNA-like chemical called RNA, that pick up instructions on how to make proteins from genes in the nucleus and deliver them to the subcellular factories which turn those proteins out. Broadly speaking, each type of messenger RNA corresponds to a single gene. By looking at the messengers Dr Crisp and Dr Boschetti could be certain they were recording active genes and not stretches of nuclear DNA that had once been genes but now no longer work.

Useful immigrants

For every transcribed messenger, they searched the world’s databases, looking for matches. They excluded the immediate relatives of each of their three groups of animals (that is, no arthropods were compared with the flies, no vertebrates with the primates and no other nematodes with the worms). They then asked whether similar-looking genes to those in a transcriptome were found more often in other animals, or in non-animals. If the former, the most likely explanation would be that they were there by common descent from animal ancestors. If the latter, then, a horizontal gene transfer from species to species seemed the most probable explanation. On average, worms had 173 horizontally transferred genes, flies had 40 and primates had 109. Humans thus had more than the primate mean.

Many of the matches are to genes of unknown purpose—for it is still the case, more than a decade after the end of the human genome project, that the jobs of many genes remain obscure. But some human transgenes are surprisingly familiar. The ABO antigen system, which defines basic blood groups for transfusion purposes, looks bacterial. The fat-mass and obesity-associated gene, the effect of which is encapsulated in its rather long-winded name, seems to come from marine algae. And a group of genes involved in the synthesis of hyaluronic acid originates from fungi. Hyaluronic acid is a chemical that is an important part of the glue which holds cells together. (It is also a frequent ingredient of skin creams.)

Altogether, the researchers found two imported genes for amino-acid metabolism, 13 for fat metabolism and 15 which are involved in the post-manufacture modification of large molecules. They also identified five immigrants that generate antioxidants and seven that are part of the immune system.

This is quite a catalogue. If anything similar were inserted by genetic engineers into corn or cattle, there would no doubt be an outcry. In humans, however, they are doing a good job. It is fair to point out that many of them seem to have been cohabiting with the line that led to humanity for millions of years, and both sides have thus had ample time to adjust. Nevertheless there was once a moment for all of them when they were just as alien as a bacterial insecticide is in a maize plant or a herbicide-resistance gene is in a soyabean.

Horizontal gene transfer: Genetically modified people | The Economist

Last edited: